When it comes to conserving the world’s oceans, bigger isn’t necessarily better. Globally, there has been an increasing trend towards placing very large marine reserves in remote regions. While these reserves help to meet some conservation targets, we don’t know if they are achieving their ultimate goal of protecting the diversity of life.

In 2002, the Convention on Biological Diversity called for at least 10% of each of the world’s land and marine habitats to be effectively conserved by 2010. Protected areas currently cover 14% of the land, but less than 3.4% of the marine environment.

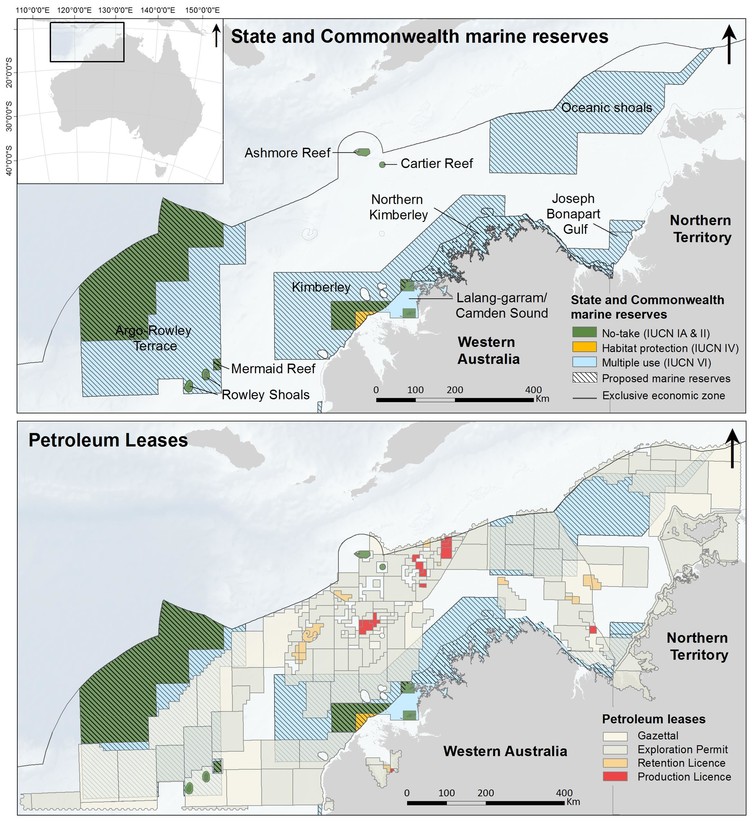

Australia’s marine reserve system covers more than a third of our oceans. This system was based on the best available information and a commitment to minimising the effects of the new protected areas on existing users. However, since its release the system has been strongly criticised for doing little to protect biodiversity, and it is currently under review.

In a new study published in Scientific Reports, we looked at the current and proposed marine reserves off northwest Australia – an area that is also home to significant oil and gas resources. Our findings show how conservation objectives could be met more efficiently. Using technical advances, including the latest spatialmodelling software, we were able to fill major gaps in biodiversity representation, with minimal losses to industry.

A delicate balance

Australia’s northwest supports important habitats such as mangrove forests, seagrass beds, coral reefs and sponge gardens. These environments support exceptionally diverse marine communities and provide important habitat for many vulnerable and threatened species, including dugongs, turtles and whale sharks.

This region also supports valuable industrial resources, including the majority of Australia’s conventional gas reserves.

A 2013 global analysis found that regions featuring both high numbers of species and large fossil fuel reserves have the greatest need for industry regulation, monitoring and conservation.

Not all protected areas contribute equally to conserving species and habitats. The level of protection can range from no-take zones (which usually don’t allow any human exploitation), to areas allowing different types and levels of activities such tourism, fishing and petroleum and mineral extraction.

A recent review of 87 marine reserves across the globe revealed that no-take areas, when well enforced, old, large and isolated, provided the greatest benefits for species and habitats. It is estimated that no-take areas cover less than 0.3% of the world’s oceans.

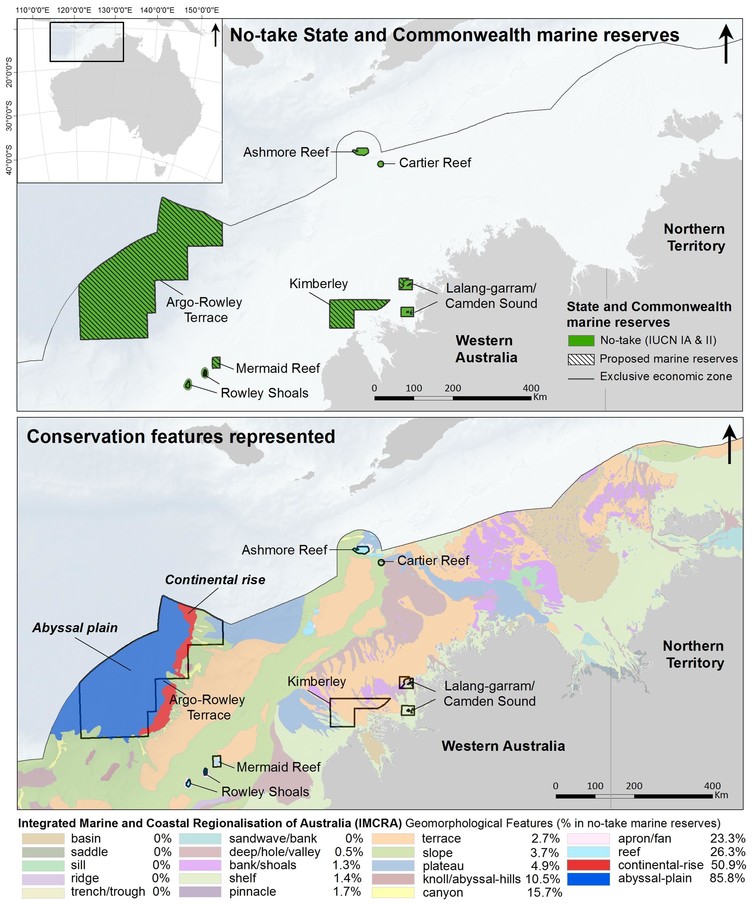

In Australia’s northwest, no-take zones cover 10.2% of the area, which is excellent by world standards in terms of size. However, an analysis of gaps in the network reveal opportunities to better meet the Convention on Biological Diversity’s recommended minimum target level of representation across all species and features of conservation interest.

We provided the most comprehensive description of the species present across the region enabling us to examine how well local species are represented within the current marine reserves. Of the 674 species examined, 98.2% had less than 10% of their habitat included within the no-take areas, while more than a third of these (227 species) had less than 2% of their habitat included.

Into the abyss

Few industries in this region operate in depths greater than 200 metres. Therefore, the habitats and biodiversity most at risk are those exposed to human activity on the continental shelf, at these shallower depths.

However, the research also found that three-quarters of the no-take marine reserves are sited over a deep abyssal plain and continental rise within the Argo-Rowley Terrace (3,000-6,000m deep). These habitats are unnecessarily over-represented (85% of the abyss is protected), as their remoteness and extreme depth make them logistically and financially unattractive for petroleum or mineral extraction anyway.

Proposed multiple-use zones in Commonwealth waters provide some much-needed extra representation of the continental shelf (0-200m depth). However, all mining activities and most commercial fishing activities are permissible pending approval. This means that the management of these multiple-use zones will require some serious consideration to ensure they are effective.

A win for conservation and industry

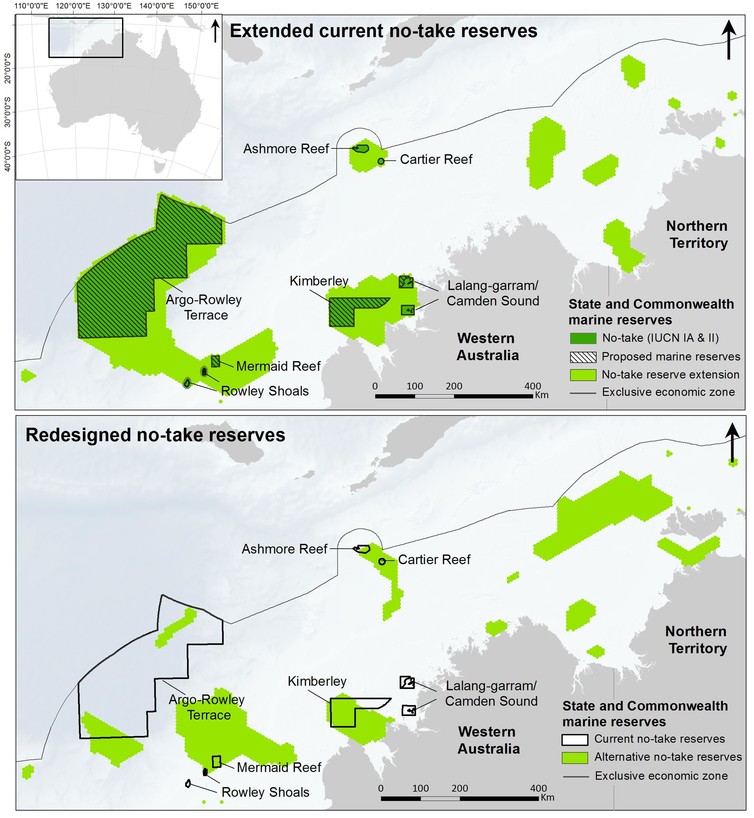

An imbalance in marine reserve representation can be driven by governments wanting to minimise socio-economic costs. But it doesn’t have to be one or the other.

Our research has shown that better zoning options can maximise the number of species while still keeping losses to industry very low. Our results show that the 10% biodiversity conservation targets could be met with estimated losses of only 4.9% of area valuable to the petroleum industry and 7.2% loss to the fishing industry (in terms of total catch in kg).

Management plans for the Commonwealth marine reserves are under review and changes that deliver win-win outcomes, like the ones we have found, should be considered.

We have shown how no-take areas in northwest Australia could either be extended or redesigned to ensure the region’s biodiversity is adequately represented. The cost-benefit analysis used is flexible and provides several alternative reserve designs. This allows for open and transparent discussions to ensure we find the best balance between conservation and industry.